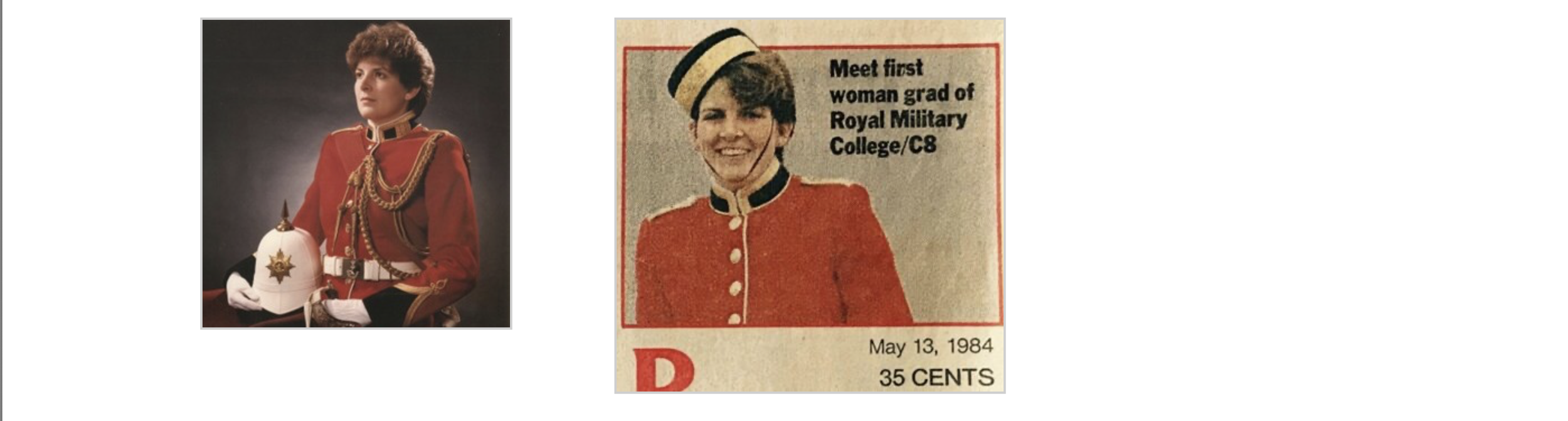

Captain Kathryn “Kate” Armstrong was the first woman to become a cadet in the history of the Royal Military College in 1980. While Armstrong was officially the first woman accepted as a cadet in 1980, she was not the only woman who enrolled as a cadet that year. Alongside Armstrong, 31 women, known collectively as “The First Thirty-Two,” became the first women officer cadets to attend RMC.

Capitaine Kathryn Armstrong, dite « Kate », fut la première femme élève-officier de l’histoire du Collège militaire royal en 1980. Même si Armstrong est officiellement la première femme à avoir été acceptée comme élève-officier en 1980, ce n’était pas la seule femme à s’enrôler comme élève-officier cette année-là. Armstrong et 31 autres femmes, connues collectivement sous le nom de « First Thirty-Two » (les Trente-deux Premières), sont devenues les premières femmes élèves-officiers à fréquenter le CMR.

In 1980, Kate Armstrong was one of 32 women who joined Royal Military College of Canada as cadets. ‘Most of us had to navigate the skepticism of superiors and fellow cadets alike. We were harassed, hazed, and tested over and over again.’

The first women’s cohort at Canada’s military colleges learned that changing laws are not synonymous with changing culture—and those same issues apply today, writes Kate Armstrong.

Across the country, photos are being posted of young people headed off to university for the first time. Forty-five years ago, in 1980, that was me, arriving at the Royal Military College of Canada, as its first female cadet. When I passed under the Arch for the first time. I was awestruck. Naively stepping into a system not designed for me, I was eager to find my place there as one of 32 women joining the ranks as recruits to become RMC cadets. No women had come before us to serve as role models, and no roadmaps existed to guide our paths.

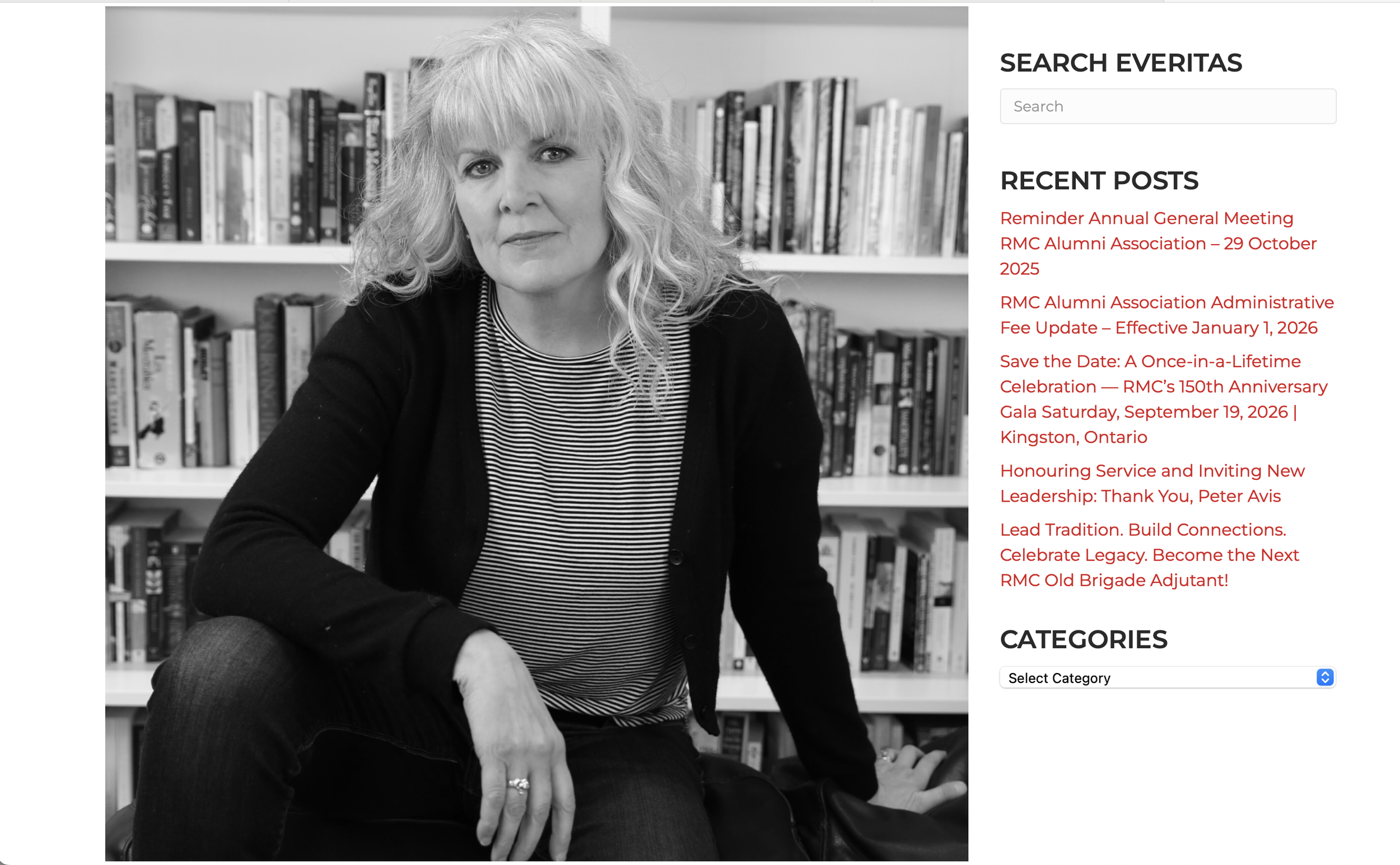

Kate Armstrong is the author of The Stone Frigate: The Royal Military College’s First Female Cadet Speaks Out, published in 2019.

We had arrived in a place steeped in history, tradition, discipline, and expectations about who belonged there and what it meant to be a cadet at RMC. For some, these expectations explicitly did not include us. Many of us were openly told that. Most of us had to navigate the skepticism of instructors, superiors, and fellow cadets alike. We were harassed, hazed, and tested over and over again, running circles around a seemingly endless track. At times, I questioned my right to be there: did I really belong?

We, the first women’s cohort at RMC, had to prove ourselves in ways our male counterparts did not. So did the first cohorts of women at the Collège militaire royal de Saint-Jean and, a few years later, at the Royal Roads Military College. Uunfortunately, this pressure continues to exist to some degree for the women attending these institutions today.

And yet we stay. We endure. We graduate.

I persevered because I knew that walking away would make it easy to conclude that the “experiment of women cadets hadn’t worked.” But it ran deeper than that. I also stayed to prove to myself and everyone else that I was smart enough, strong enough, and “good” enough to be a valuable contributing member in a traditionally male-dominated world. Sadly, I carried the belief for decades that I needed to prove I was “one of the boys” to add value in my work environments and my world. It took time for me to learn to be comfortable in my skin and with my own way of interacting with the world.

We discovered back then that changing laws and entrance requirements is not synonymous with changing culture and norms. Both are necessary, and the latter is significantly more challenging. Moreover, it is not a “once and done” proposition. Recently, the Canadian Military Colleges Review Board (CMCRB) made clear in its report that the colleges still have a lot of work to do to become safe and inclusive places for all, and that RMC governance structures must be updated to support the necessary changes across the board.

The ability to give meaningful directions to anyone who is lost requires answering a simple question: “Where are you now?” The CMCRB report delineates the state of RMC in unwavering honesty. I was heartened to read it. In my view, it offers a pragmatic approach to righting the ship—I feel that we could finally be heading in the right direction.

Making these changes is worthwhile. Even as I wrote my 2019 memoir, The Stone Frigate: The Royal Military College’s First Female Cadet Speaks Out, I grieved an anticipated backlash that might make me persona non grata at these colleges. I persevered in writing my story not because I hated RMC or was bitter about my time there, but rather because of my heartfelt belief that genuine cultural change for all Canadians was possible from within those walls. I echo the CMCRB’s findings that, culturally, military colleges are largely the place—not the reason—that misconduct happens.

The colleges have been—and must continue to be—a place of transformation, not just for the students who pass through their halls, but also for the culture in our military and our broader society. The CMCRB makes a statement that captures the essence of what needs to be done: action must match rhetoric in fact and in perception. The mission to produce leaders of character, ready to serve Canada, remains as relevant today as it was 45 years ago, as it has been since 1876.

The time for concrete action is now. The path forward is laid out in the CMCRB, and requires dedication, persistence, and a relentless drive for progress. By standing behind the colleges, we can ensure that the evolving face of leadership in Canada reflects those who serve and all of us who depend upon them.

Truth. Duty. Valour. Taken alone, these are just words. Taken to heart, these words can change the world.